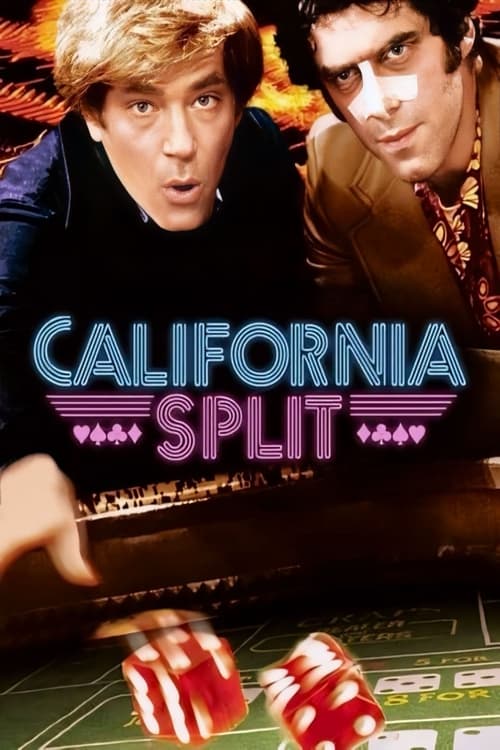

California Split

Carefree single guy Charlie Waters rooms with two lovely prostitutes, Barbara Miller and Susan Peters, and lives to gamble. Along with his glum betting buddy, Bill Denny, Charlie sets out on a gambling streak in search of the ever-elusive big payday. While Charlie and Bill have some lucky moments, they also have to contend with serious setbacks that threaten to derail their hedonistic betting binge.

The film earned $5.0M at the global box office.

Plot Structure

Story beats plotted across runtime

Narrative Arc

Emotional journey through the story's key moments

Story Circle

Blueprint 15-beat structure

Arcplot Score Breakdown

Weighted: Precision (70%) + Arc (15%) + Theme (15%)

California Split (1974) exemplifies precise narrative design, characteristic of Robert Altman's storytelling approach. This structural analysis examines how the film's 15-point plot structure maps to proven narrative frameworks across 1 hour and 48 minutes. With an Arcplot score of 6.7, the film balances conventional beats with creative variation.

Characters

Cast & narrative archetypes

Bill Denny

Charlie Waters

Main Cast & Characters

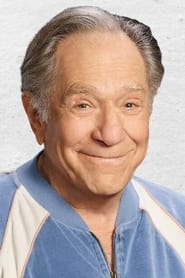

Bill Denny

Played by George Segal

A magazine writer and compulsive gambler who gets drawn into a chaotic friendship with Charlie that spirals into a high-stakes gambling odyssey.

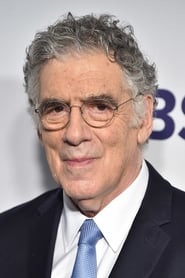

Charlie Waters

Played by Elliott Gould

A charismatic, free-spirited professional gambler who lives from bet to bet and introduces Bill to a wilder, more reckless lifestyle.

Structural Analysis

The Status Quo at 1 minutes (1% through the runtime) establishes Bill Denny sits alone at a poker table in a smoky California card room, a compulsive gambler living a solitary, routine existence defined by the next bet.. Of particular interest, this early placement immediately immerses viewers in the story world.

The inciting incident occurs at 13 minutes when Bill meets Charlie Waters, a charismatic, reckless gambler with an opposite philosophy - all instinct and impulse. Charlie's infectious energy andfreewheeling approach to gambling represents everything Bill has suppressed.. At 12% through the film, this Disruption aligns precisely with traditional story structure. This beat shifts the emotional landscape, launching the protagonist into the central conflict.

The First Threshold at 27 minutes marks the transition into Act II, occurring at 25% of the runtime. This illustrates the protagonist's commitment to Bill makes the active choice to fully embrace Charlie's lifestyle, moving in and becoming partners in their gambling adventures. He abandons his conventional life to pursue the action full-time., moving from reaction to action.

At 54 minutes, the Midpoint arrives at 50% of the runtime—precisely centered, creating perfect narrative symmetry. Significantly, this crucial beat A brutal losing streak and mounting debts. Bill faces consequences from his conventional life - his wife calls, work responsibilities loom. The false victory of "freedom" reveals its costs. The stakes become real and dangerous., fundamentally raising what's at risk. The emotional intensity shifts, dividing the narrative into clear before-and-after phases.

The Collapse moment at 81 minutes (75% through) represents the emotional nadir. Here, Bill and Charlie are broke, beaten down, facing the emptiness beneath the action. The dream of the big score has died. Bill confronts the reality that gambling hasn't filled the void - it's only deepened it., indicates the protagonist at their lowest point. This beat's placement in the final quarter sets up the climactic reversal.

The Second Threshold at 86 minutes initiates the final act resolution at 80% of the runtime. Bill gets one final stake - a trip to Reno for the ultimate score. He synthesizes his careful strategy with Charlie's boldness for one last run. This time he'll know whether winning can actually satisfy him., demonstrating the transformation achieved throughout the journey.

Emotional Journey

California Split's emotional architecture traces a deliberate progression across 15 carefully calibrated beats.

Narrative Framework

This structural analysis employs structural analysis methodology used to understand storytelling architecture. By mapping California Split against these established plot points, we can identify how Robert Altman utilizes or subverts traditional narrative conventions. The plot point approach reveals not only adherence to structural principles but also creative choices that distinguish California Split within the comedy genre.

Robert Altman's Structural Approach

Among the 10 Robert Altman films analyzed on Arcplot, the average structural score is 6.9, demonstrating varied approaches to story architecture. California Split takes a more unconventional approach compared to the director's typical style. For comparative analysis, explore the complete Robert Altman filmography.

Comparative Analysis

Additional comedy films include The Bad Guys, Ella Enchanted and The Evening Star. For more Robert Altman analyses, see Cookie's Fortune, Dr. T & the Women and Nashville.

Plot Points by Act

Act I

SetupStatus Quo

Bill Denny sits alone at a poker table in a smoky California card room, a compulsive gambler living a solitary, routine existence defined by the next bet.

Theme

Charlie Waters tells Bill, "You're looking for the action, but you don't know what to do when you find it" - establishing the theme about seeking thrills versus finding meaning.

Worldbuilding

Introduction to the underground gambling world of Los Angeles - poker rooms, racetracks, bars. Bill's controlled, measured approach contrasts with the chaotic energy around him. His conventional life as a magazine writer conflicts with his gambling compulsion.

Disruption

Bill meets Charlie Waters, a charismatic, reckless gambler with an opposite philosophy - all instinct and impulse. Charlie's infectious energy andfreewheeling approach to gambling represents everything Bill has suppressed.

Resistance

Bill resists Charlie's chaotic lifestyle while being drawn to it. Charlie introduces Bill to his world - his prostitute roommates Barbara and Susan, late-night poker games, constant action. Bill struggles between his structured life and the allure of total immersion in gambling.

Act II

ConfrontationFirst Threshold

Bill makes the active choice to fully embrace Charlie's lifestyle, moving in and becoming partners in their gambling adventures. He abandons his conventional life to pursue the action full-time.

Mirror World

The relationship with Charlie and his world - particularly the easy companionship with Barbara and Susan - shows Bill what a life without walls looks like. Charlie becomes the mirror showing Bill his own hidden desires for freedom and spontaneity.

Premise

The "fun and games" of the gambling life - winning and losing streaks, boxing matches, track betting, poker tournaments. Bill and Charlie's partnership deepens as they ride the waves of chance together, experiencing the pure pleasure of action and risk.

Midpoint

A brutal losing streak and mounting debts. Bill faces consequences from his conventional life - his wife calls, work responsibilities loom. The false victory of "freedom" reveals its costs. The stakes become real and dangerous.

Opposition

Pressure intensifies as debts mount and Bill's two worlds collide. Charlie's lifestyle becomes increasingly desperate rather than liberating. The partnership strains as Bill's caution conflicts with Charlie's recklessness. They scramble to stay ahead, but the house always wins.

Collapse

Bill and Charlie are broke, beaten down, facing the emptiness beneath the action. The dream of the big score has died. Bill confronts the reality that gambling hasn't filled the void - it's only deepened it.

Crisis

Bill sits in darkness with his losses, questioning everything. Charlie remains in denial, still chasing. Bill processes whether the freedom he sought was real or just another compulsion wearing a different mask.

Act III

ResolutionSecond Threshold

Bill gets one final stake - a trip to Reno for the ultimate score. He synthesizes his careful strategy with Charlie's boldness for one last run. This time he'll know whether winning can actually satisfy him.

Synthesis

The Reno finale - Bill goes on an incredible winning streak, hitting the big score he's always dreamed of. He wins thousands, beating the house, achieving the gambler's fantasy. Charlie celebrates wildly beside him.

Transformation

Bill walks away from the big win feeling completely empty, telling Charlie "I don't feel anything." The victory is hollow. He's learned that the action itself was the addiction, not the solution. Winning changed nothing inside him.