Story Structures: A Deeper Look

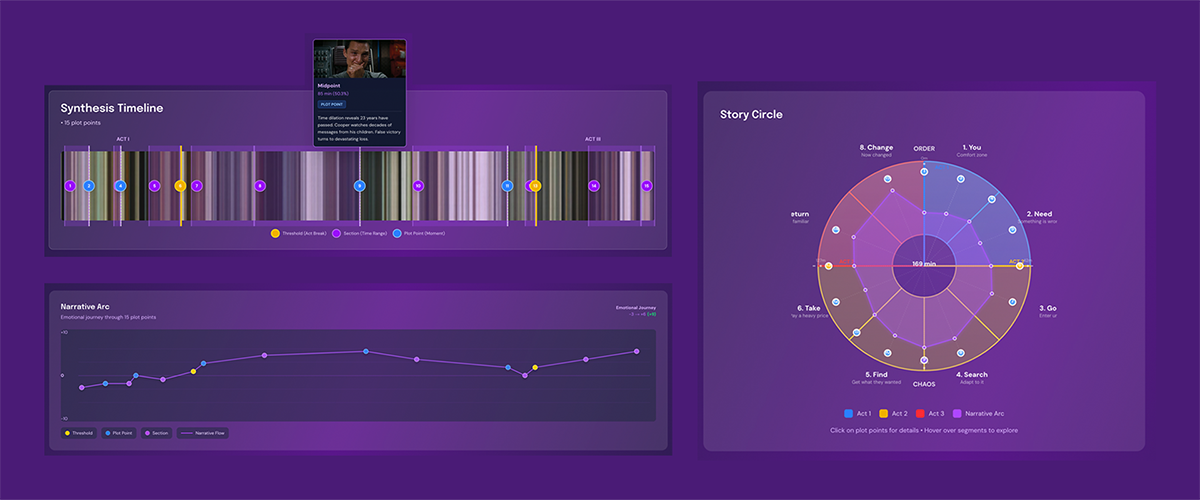

Introducing narrative frameworks Arcplot uses to visualize story structure. The origins, mechanics, and how stories work. The meta structure in the west: The Hero's Journey and two simplified templates for plotting short-form narratives: the Narrative Synthesis and the Story Circle

On our main About page, we introduced the narrative frameworks Arcplot uses to visualize story structure. Here, we'll go further into each one: its origins, its mechanics, and what it reveals (or claims to reveal) about how stories work.

The Hero's Journey

Origins and History

The Hero's Journey, also called the monomyth, was popularized by mythologist Joseph Campbell in his 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Campbell drew on the analytical psychology of Carl Jung, the psychoanalytic work of Otto Rank, and decades of comparative mythology to argue that hero stories across cultures share a common underlying structure. The claim was bold, maybe too bold, but it stuck.

Campbell borrowed the term "monomyth" from James Joyce's Finnegans Wake, and his work built on earlier scholarship by anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor (1871) and German philologist Johann Georg von Hahn (1876), who had observed recurring patterns in hero narratives across Indo-European traditions. So even the theory of universal story structure has its own lineage, its own intellectual genealogy tracing back through generations of people noticing that certain shapes kept showing up.

The Hero's Journey entered mainstream consciousness through two documentaries: The Hero's Journey: The World of Joseph Campbell (1987) and Bill Moyers' The Power of Myth (1988). George Lucas famously credited Campbell's work as a direct influence on Star Wars, saying he began to realize his first draft "was following classical motifs" after reading Campbell's book. Whether Lucas discovered Campbell's pattern or imposed it retroactively is a question worth sitting with.

The 17 Stages

Campbell originally described 17 stages, organized into three major movements. Not every story contains all 17. Some focus on only a few, others reorder them, and many successful narratives ignore entire sections. But the overall shape, Campbell argued, remains recognizable if you know how to look.

Act I: Departure (Separation)

The Call to Adventure — The hero receives information that pulls them toward the unknown: a message, a discovery, a disruption to ordinary life. Something arrives that cannot be un-arrived.

Refusal of the Call — Fear, duty, or insecurity causes the hero to hesitate. Campbell wrote that refusing the call "converts the adventure into its negative," meaning the hero becomes trapped rather than transformed. The refusal is itself a kind of choice, even if it feels like paralysis.

Supernatural Aid — A mentor or helper appears, often providing talismans, advice, or protection. This figure represents what Campbell called "the benign, protecting power of destiny." Whether you find that comforting or ominous probably says something about you.

Crossing the First Threshold — The hero commits to the journey, leaving the known world behind. Beyond this point lie darkness, the unknown, and danger. The threshold is both literal and metaphorical, and the crossing is rarely clean.

The Belly of the Whale — A symbolic death and rebirth. The hero is swallowed into the unknown and must demonstrate willingness to undergo metamorphosis. Think Jonah. Think Luke Skywalker in the Death Star's trash compactor. The point is that you cannot enter the underworld and remain who you were.

Act II: Initiation (Descent)

The Road of Trials — A series of tests the hero must survive. These often come in threes, and the hero frequently fails before succeeding. The failures matter as much as the successes. Maybe more.

The Meeting with the Goddess — An encounter with a figure representing unconditional love or the life force itself. Campbell describes this as "the final test of the talent of the hero to win the boon of love." The gendered language is Campbell's, and it has not aged gracefully, but the underlying idea (that the hero must prove capable of receiving something freely given) remains interesting.

Woman as Temptress — Temptations that could derail the quest. Not necessarily literal women, despite Campbell's framing, but anything representing material or physical distraction from the spiritual journey. The temptation is always toward the easier path, the one that doesn't require transformation.

Atonement with the Father — The hero confronts whatever holds ultimate power over their life. This is the center point of the journey: everything before leads here, everything after flows from it. Campbell saw this as the crisis of identity, the moment when the hero must face the source of their own fear.

Apotheosis — A moment of divine knowledge or expanded awareness. The hero achieves a greater understanding that prepares them for what comes next. The word literally means "becoming god," which is grandiose, but the experience is more like suddenly seeing the whole board instead of just your piece.

The Ultimate Boon — The achievement of the quest's goal: the elixir, the grail, the knowledge, the treasure. Everything has built to this acquisition. And yet the acquisition is rarely the point. The point is who you had to become to acquire it.

Act III: Return

Refusal of the Return — Having found bliss or enlightenment, the hero may not want to return to ordinary life. Why would you? The ordinary world is where you were before you knew what you now know.

The Magic Flight — If the boon was stolen or the gods oppose the return, the journey home becomes its own adventure of pursuit and escape. The return is never just a reversal of the departure.

Rescue from Without — Sometimes the hero needs help returning to the ordinary world, especially if wounded or transformed beyond recognition. You cannot always pull yourself out.

Crossing the Return Threshold — The hero must survive the impact of re-entering the ordinary world and integrate the wisdom gained. This is harder than it sounds. The world didn't change while you were gone. You did.

Master of Two Worlds — The hero achieves balance between the inner and outer worlds, comfortable in both realms. This is the ideal outcome, the state of having been transformed without being destroyed.

Freedom to Live — Mastery over fear of death leads to freedom to live fully in the present moment. Campbell saw this as the ultimate goal: not immortality, but the ability to exist without being paralyzed by mortality.

Criticisms and Limitations

Campbell's monomyth has faced significant scholarly criticism, and some of it sticks. Folklorists like Barre Toelken and Alan Dundes have argued that Campbell selected stories that fit his theory while ignoring those that didn't. This is a serious charge. If you're claiming to have found a universal pattern, you can't just skip the counterexamples.

Others note that the framework can be so vague as to fit almost anything, which raises the question of whether it's actually predicting anything or just providing a vocabulary for pattern-matching after the fact. A map that describes every possible territory isn't really a map.

Feminist critics have developed alternative frameworks like Maureen Murdock's The Heroine's Journey (1990) and Kim Hudson's The Virgin's Promise, arguing that the monomyth centers masculine experiences of external conquest rather than feminine patterns of internal awakening. Artist Alice Meichi Li has pointed out that the hero's journey is fundamentally "the journey of someone who has privilege," and that characters without social power may complete their transformation only to return to a world that still oppresses them.

Despite these critiques, the Hero's Journey remains influential precisely because it captures something real about transformation narratives. That something is probably more flexible and culturally variable than Campbell suggested. But it's still something.

Narrative Synthesis

The Three-Act Structure and Hegelian Dialectic

The three-act structure didn't originate in Hollywood, or even in theater. Its philosophical architecture goes back at least to Hegel's dialectic: Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis.

Act I is Thesis. A world exists in a certain state. The protagonist has a particular relationship to that world. This is the given, the starting conditions, what is.

Act II is Antithesis. The protagonist enters a new situation that contradicts or challenges the thesis. The old rules don't apply. The familiar self doesn't work. This is the negation, the thing that cannot coexist with what came before.

Act III is Synthesis. The protagonist integrates what they learned in the contradiction. They return to the ordinary world transformed, carrying something from the antithesis back into the thesis. This is the resolution, but not a simple return to Act I. The circle closes at a higher level.

This pattern appears everywhere. In Greek tragedy, where the exposition (thesis) gives way to rising conflict (antithesis) and ends in catharsis (synthesis). In Shakespearean drama, where five acts essentially stretch the three-act shape across more granular movements. In nearly every story you can think of that involves change.

The Hero's Journey maps perfectly onto this structure: Departure is thesis, Initiation is antithesis, Return is synthesis. Dan Harmon's Story Circle makes it even more explicit, with the top half of the circle representing order (thesis) and the bottom half chaos (antithesis), and the return journey synthesizing the two.

The Beat Sheet comes from Blake Snyder's 2005 book Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You'll Ever Need. The title is confident to the point of audacity, which tells you something about Snyder's approach. He was a Hollywood screenwriter known for selling scripts (including Blank Check for Disney), and he developed his beat sheet by reverse-engineering the structure of successful films.

The "save the cat" concept refers to a screenwriting technique: early in a story, have your protagonist do something admirable (like saving a cat) to make the audience root for them. Snyder pointed to the opening of Aliens, where Ripley risks her life to save her cat Jonesy, as a perfect example. The same principle appears in Aladdin, when the thief gives his stolen bread to starving children. You're manipulating the audience, yes, but the manipulation works because it taps into something genuine about how we form attachments.

Snyder passed away suddenly in 2009, but his system has continued to grow through sequels written by his students and collaborators. The franchise now includes guides for novels, television, and genre-specific applications. It has become, somewhat ironically, exactly the kind of institutionalized formula that indie filmmakers love to rebel against.

Snyder takes the vague, intimidating middle section (the antithesis, the chaos, the long desert of Act II) and break it into discrete, diagnosable, teachable moments. He gave islands and shorter swims. He made the structure legible to people who didn't have the time or inclination to read Campbell or Hegel.

This is both the genius and the limitation of the Beat Sheet. It's extraordinarily useful for the problem it was designed to solve: making commercial films that hold an audience's attention for two hours. It's less useful for understanding why stories have the shape they do in the first place, because that question predates Hollywood by several thousand years.

The 15 Beats

Snyder designed his beat sheet to solve a common screenwriting problem: the vast, formless second act. Three-act structure gives you only two major turning points, which means the middle of your story is a desert you have to cross with minimal landmarks. Snyder's 15 beats create what he called "more islands, shorter swims."

Each beat includes a suggested page number for a 110-page screenplay, which translates roughly to percentage of total runtime. The precision is part of the appeal. It's also part of what makes some writers uncomfortable.

Act I (Pages 1-25)

Opening Image (p. 1) — A visual snapshot of the protagonist's world before the adventure begins. Sets tone and establishes what will change. The opening image and the final image should rhyme.

Theme Stated (p. 5) — Someone (often not the protagonist) states the film's thematic premise, usually in a way the protagonist doesn't yet understand. The theme is hiding in plain sight, waiting to be recognized.

Set-Up (pp. 1-10) — Establish the protagonist's world, relationships, and what's missing from their life. Introduce every character who will matter later. You're laying pipe, which is tedious but necessary.

Catalyst (p. 12) — The event that sets the story in motion. A message arrives, a discovery is made, something happens that cannot be ignored. This is the thing that, once it happens, makes the old life impossible.

Debate (pp. 12-25) — The protagonist hesitates. Should they accept the call? What will it cost? This section asks the question the rest of the film will answer. The debate is internal even when it looks external.

Break into Two (p. 25) — The protagonist makes a choice and enters Act II. Snyder insisted this must be a decision, not something that happens to them. Agency matters.

Act II (Pages 25-85)

B Story (p. 30) — A subplot begins, often a love story, that will carry the film's theme. The B Story characters frequently deliver the thematic lesson the protagonist needs to learn. They're teachers disguised as distractions.

Fun and Games (pp. 30-55) — The "promise of the premise." If your movie is about a cop and a dog, this is where we see the cop and the dog doing cop-and-dog things. Often the most memorable sequences. Often what's in the trailer.

Midpoint (p. 55) — A major shift. Either a false victory (things seem great but aren't) or a false defeat (things seem terrible but aren't). Stakes are raised. The protagonist moves from "wanting" to "needing," though they may not realize it yet.

Bad Guys Close In (pp. 55-75) — External pressure intensifies while internal doubts grow. The team fractures. Enemies regroup. Everything gets harder. This is where stories often sag, which is why Snyder paid so much attention to it.

All Is Lost (p. 75) — The opposite of the Midpoint. If Midpoint was a false victory, this is a real defeat. Often involves what Snyder called a "whiff of death," meaning someone dies, or something representing the old way of life does. The hero must lose something they cannot get back.

Dark Night of the Soul (pp. 75-85) — The protagonist hits bottom. Wallowing in hopelessness. This is the darkness before the dawn, the moment when transformation becomes possible precisely because everything else has failed.

Break into Three (p. 85) — A new idea or revelation emerges, often from the B Story. The protagonist sees the solution and commits to the final push. The answer was there all along; they just couldn't see it.

Act III (Pages 85-110)

Finale (pp. 85-110) — The protagonist executes the plan, applying everything learned. Subplots resolve. The antagonist is defeated not just physically but thematically. Snyder broke this into five sub-beats for additional granularity, because he was that kind of person.

Final Image (p. 110) — A visual that mirrors the Opening Image but shows how everything has changed. Proof of transformation. The rhyme completes.

Strengths and Limitations

The Beat Sheet excels at diagnosing pacing problems. If your second act sags, the beat sheet can tell you exactly which island you're missing. It's particularly useful for commercial filmmaking, where timing and audience engagement are paramount and where the difference between a film that works and one that doesn't can come down to structural mechanics.

Critics argue that rigid adherence to the beat sheet produces formulaic, predictable stories. There's truth to this. You can feel a beat sheet film sometimes, feel the machinery turning beneath the surface. Snyder acknowledged this concern but maintained that structure and creativity aren't opposites. The beat sheet is scaffolding, not a straitjacket. Whether you believe him probably depends on how many beat sheet films you've sat through.

The Story Circle

Origins and History

The Story Circle was developed by Dan Harmon, creator of Community and co-creator of Rick and Morty, while he was stuck on a screenplay in the late 1990s. Frustrated, he began looking for what he described as "some symmetry, some simplicity" underlying successful stories. The search was partly practical (he needed to finish the script) and partly obsessive (he couldn't stop thinking about it).

Later, while running Channel 101 (a short-film competition he co-founded), Harmon noticed that many directors claimed they couldn't write plots. This struck him as strange. Plots aren't that complicated if you know what you're doing. So he responded by distilling Joseph Campbell's Hero's Journey into an eight-step circle simple enough to explain in minutes and versatile enough to apply to almost anything.

Harmon has said the circle is now "tattooed on my brain." He can't watch or write a story without seeing it. He's used it extensively on both Community and Rick and Morty, where whiteboards in the writers' room show episodes broken down into its eight segments. The circle has become both a tool and a compulsion, which is perhaps the fate of anyone who spends enough time thinking about structure.

The 8 Steps

The Story Circle arranges its beats in a literal circle, with the top half representing order and the bottom half representing chaos. The protagonist descends into chaos and returns transformed. Or doesn't return. Or returns unchanged. The circle describes the pattern; what happens within it is up to you.

YOU — A character in a zone of comfort or familiarity. We establish who they are and what their normal looks like. Normal is always more fragile than it appears.

NEED — But they want something. Something is wrong, missing, or desired. This want will drive them forward. The want doesn't have to be noble. It doesn't even have to be conscious.

GO — They enter an unfamiliar situation. They cross a threshold into new territory, physical, emotional, or both. The crossing is the commitment.

SEARCH — They adapt to the new situation. They learn its rules, face its challenges, struggle to survive or succeed. This is the work of being somewhere you don't belong.

FIND — They get what they wanted. The goal is achieved, or seems to be. This often occurs at or near the story's midpoint. The finding is rarely what they expected.

TAKE — But they pay a heavy price. Getting what you want costs something. Victory has consequences. The price is often the thing you didn't know you were betting.

RETURN — They go back to their familiar situation. Armed with new knowledge, they re-enter the world they left. The world hasn't changed. They have. This creates friction.

CHANGE — Having changed as a result of the journey. They are not the person who left. The circle closes, but the character has been transformed. Whether the transformation is good is a separate question.

The Circle as Psychology

Where the Beat Sheet focuses on plot mechanics, the Story Circle emphasizes psychological transformation. Harmon has described the bottom half of the circle (steps 4 through 6) using Campbell's imagery: "a digestive tract, breaking the hero down, divesting him of neuroses, stripping him of fear and desire." The metaphor is visceral. The descent is supposed to be uncomfortable. That's how you know it's working.

The simplicity is intentional. Harmon designed the circle so that even someone who claims they "can't write" can use it to generate a coherent story. The eight steps are loose enough to accommodate almost any premise while tight enough to guarantee forward momentum. It's a minimum viable structure, the smallest set of beats you need to create something that feels complete.

Film vs. Television

Harmon notes that the Story Circle works differently across media. In film, the goal is to send the audience out of the theater transformed. Step 8 should feel like a genuine ending, a door closing behind you. In television, the goal is to keep viewers returning. Step 8 often returns characters close to where they started, resetting for the next episode while still suggesting incremental change.

This is why television circles can feel "irritatingly predictable," as Harmon puts it. The structure is even more visible when repeated weekly. But that predictability is also comforting, part of what makes episodic television feel like returning home. You know the shape. You trust the shape. The pleasure is in watching how each episode fills it differently.

How the Frameworks Relate

All three frameworks share DNA. The Hero's Journey is the mythological ancestor, drawing on Jungian archetypes and comparative religion. The Beat Sheet is its Hollywood adaptation, adding precision timing and commercial considerations. The Story Circle is its minimalist descendant, stripping away everything except the essential shape of transformation.

Each framework also has a different emphasis: The Hero's Journey focuses on meaning: what transformation represents spiritually and psychologically. It asks why stories take the shapes they do.

The Beat Sheet focuses on craft: when specific events should occur to maximize engagement. It asks how to build something that works.

The Story Circle focuses on simplicity: the irreducible core of what makes a story feel complete. It asks what you can't leave out.

You can map any story onto any of these frameworks, with varying degrees of strain. The question isn't which one is "correct" but which lens illuminates what you're trying to see. A microscope and a telescope are both useful. They're just useful for different things.

A Note on Using These Frameworks

At Arcplot, we use these structures as analytical tools, not quality metrics. A film can follow the Beat Sheet perfectly and still feel hollow. An episode can "score" poorly against the Hero's Journey and still become a cultural touchstone. The frameworks describe patterns that many successful stories share, but correlation isn't causation, and fitting a template isn't the same as making something good.

These patterns exist because they resonate with something in human psychology. But the resonance comes from meaning, character, and craft, not from hitting beats in the right order. The structure is necessary but not sufficient. It's the skeleton, not the soul.

Use these structures to understand stories better, not to reduce them to checkboxes. And be suspicious of anyone, including us, who claims to have found the one true formula. Stories are older than formulas, and they'll outlast them too.

Want to see how your favorite films map to these frameworks? Explore our movie database to compare story structures across cinema history.