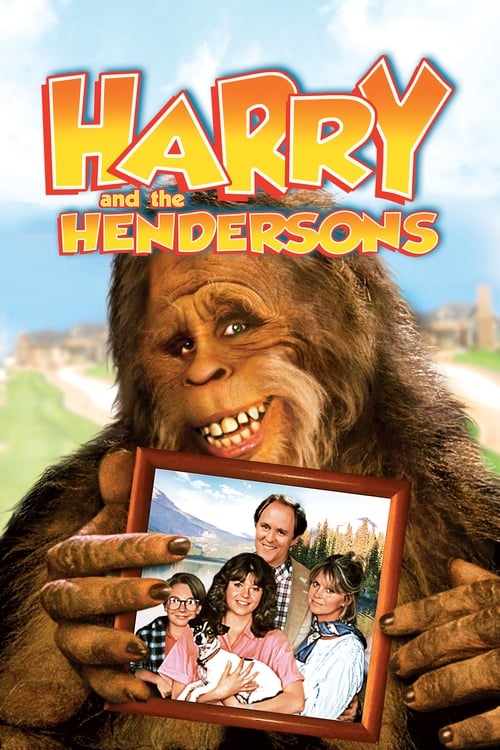

Harry and the Hendersons

Returning from a hunting trip in the forest, the Henderson family's car hits an animal in the road. At first they fear it was a man, but when they examine the "body" they find it's a "bigfoot". They think it's dead so they decide to take it home (there could be some money in this). As you guessed, it isn't dead. Far from being the ferocious monster they fear "Harry" to be, he's a friendly giant.

Despite its modest budget of $10.0M, Harry and the Hendersons became a commercial success, earning $50.0M worldwide—a 400% return. The film's unique voice connected with viewers, showing that strong storytelling can transcend budget limitations.

1 Oscar. 2 wins & 7 nominations

Plot Structure

Story beats plotted across runtime

Narrative Arc

Emotional journey through the story's key moments

Story Circle

Blueprint 15-beat structure

Arcplot Score Breakdown

Weighted: Precision (70%) + Arc (15%) + Theme (15%)

Harry and the Hendersons (1987) exemplifies precise story structure, characteristic of William Dear's storytelling approach. This structural analysis examines how the film's 15-point plot structure maps to proven narrative frameworks across 1 hour and 50 minutes. With an Arcplot score of 7.3, the film balances conventional beats with creative variation.

Characters

Cast & narrative archetypes

George Henderson

Harry

Nancy Henderson

Ernie Henderson

Sarah Henderson

Jacques LaFleur

Main Cast & Characters

George Henderson

Played by John Lithgow

A suburban father who discovers and befriends Bigfoot after hitting him with the family car

Harry

Played by Kevin Peter Hall

A gentle Sasquatch who becomes part of the Henderson family, learning to adapt to human society

Nancy Henderson

Played by Melinda Dillon

George's supportive wife who initially resists but grows to love Harry

Ernie Henderson

Played by Joshua Rudoy

The teenage son who bonds with Harry and helps protect him

Sarah Henderson

Played by Margaret Langrick

The young daughter who immediately accepts Harry as part of the family

Jacques LaFleur

Played by David Suchet

A hardened cryptozoologist and Bigfoot hunter obsessed with capturing a Sasquatch

Structural Analysis

The Status Quo at 1 minutes (1% through the runtime) establishes The Henderson family - George, Nancy, and their children - drive through the Pacific Northwest on a camping vacation, representing a typical suburban family enjoying outdoor recreation.. Notably, this early placement immediately immerses viewers in the story world.

The inciting incident occurs at 12 minutes when The Hendersons accidentally hit what they believe is a Bigfoot with their car on a dark forest road, killing it. They decide to strap the creature to their roof and bring it home.. At 11% through the film, this Disruption aligns precisely with traditional story structure. This beat shifts the emotional landscape, launching the protagonist into the central conflict.

The First Threshold at 27 minutes marks the transition into Act II, occurring at 25% of the runtime. This demonstrates the protagonist's commitment to George makes the active choice to protect Harry instead of turning him over to authorities or scientists. The family commits to hiding and caring for the creature they name "Harry."., moving from reaction to action.

At 54 minutes, the Midpoint arrives at 49% of the runtime—precisely centered, creating perfect narrative symmetry. Of particular interest, this crucial beat Harry escapes into the city streets of Seattle, causing public panic and drawing the attention of bigfoot hunter Jacques LaFleur. The stakes escalate as Harry becomes a target and the secret is exposed., fundamentally raising what's at risk. The emotional intensity shifts, dividing the narrative into clear before-and-after phases.

The Collapse moment at 80 minutes (73% through) represents the emotional nadir. Here, LaFleur corners Harry and is about to shoot him. George realizes that keeping Harry in civilization will lead to his death - either he'll be killed or live in captivity. George's dream of coexistence collapses., indicates the protagonist at their lowest point. This beat's placement in the final quarter sets up the climactic reversal.

The Second Threshold at 88 minutes initiates the final act resolution at 80% of the runtime. George synthesizes his hunting instincts with his newfound respect for nature: he will use his tracking skills not to capture or kill, but to return Harry safely to the wilderness and protect him from LaFleur., demonstrating the transformation achieved throughout the journey.

Emotional Journey

Harry and the Hendersons's emotional architecture traces a deliberate progression across 15 carefully calibrated beats.

Narrative Framework

This structural analysis employs proven narrative structure principles that track dramatic progression. By mapping Harry and the Hendersons against these established plot points, we can identify how William Dear utilizes or subverts traditional narrative conventions. The plot point approach reveals not only adherence to structural principles but also creative choices that distinguish Harry and the Hendersons within the comedy genre.

William Dear's Structural Approach

Among the 4 William Dear films analyzed on Arcplot, the average structural score is 7.0, demonstrating varied approaches to story architecture. Harry and the Hendersons represents one of the director's most structurally precise works. For comparative analysis, explore the complete William Dear filmography.

Comparative Analysis

Additional comedy films include The Bad Guys, Ella Enchanted and The Evening Star. For more William Dear analyses, see A Mile in His Shoes, Angels in the Outfield and If Looks Could Kill.

Plot Points by Act

Act I

SetupStatus Quo

The Henderson family - George, Nancy, and their children - drive through the Pacific Northwest on a camping vacation, representing a typical suburban family enjoying outdoor recreation.

Theme

George discusses hunting and his desire to bag "the big one," while Nancy questions the ethics of killing animals for sport, establishing the theme of humanity's relationship with nature and wildlife.

Worldbuilding

Introduction to the Henderson family dynamics: George as the hunter/outdoorsman, Nancy as the caring mother, their children's personalities, and their comfortable suburban Seattle lifestyle.

Disruption

The Hendersons accidentally hit what they believe is a Bigfoot with their car on a dark forest road, killing it. They decide to strap the creature to their roof and bring it home.

Resistance

The family debates what to do with the creature - should they display it, sell it to science, or keep it secret? The "dead" Bigfoot comes alive in their home, terrifying and confusing the family.

Act II

ConfrontationFirst Threshold

George makes the active choice to protect Harry instead of turning him over to authorities or scientists. The family commits to hiding and caring for the creature they name "Harry."

Mirror World

George begins bonding with Harry, seeing him not as a trophy or commodity but as a sentient being worthy of respect and protection. Harry becomes the embodiment of nature deserving humanity's compassion.

Premise

The fun of living with Bigfoot: Harry destroys the house, learns to interact with the family, causes chaos in the neighborhood, and the Hendersons attempt to domesticate and hide him while growing attached.

Midpoint

Harry escapes into the city streets of Seattle, causing public panic and drawing the attention of bigfoot hunter Jacques LaFleur. The stakes escalate as Harry becomes a target and the secret is exposed.

Opposition

LaFleur closes in on Harry; the media frenzy intensifies; George's work and family life suffer; neighbors become suspicious; the family struggles to recapture Harry and keep him safe from hunters.

Collapse

LaFleur corners Harry and is about to shoot him. George realizes that keeping Harry in civilization will lead to his death - either he'll be killed or live in captivity. George's dream of coexistence collapses.

Crisis

George grieves the realization that loving Harry means letting him go. The family processes that true compassion requires sacrifice and that Harry belongs in the wild, not in their world.

Act III

ResolutionSecond Threshold

George synthesizes his hunting instincts with his newfound respect for nature: he will use his tracking skills not to capture or kill, but to return Harry safely to the wilderness and protect him from LaFleur.

Synthesis

The family executes a plan to lead Harry back to the forest; George confronts LaFleur and convinces him to abandon his hunt; the final goodbye as Harry returns to his natural habitat; resolution with authorities.

Transformation

George stands in the forest watching Harry disappear into the wilderness. The former hunter has become a protector of wildlife, transformed by his relationship with a creature he once would have killed.